Recently I was reminded of a story that Dmitri told us and which apparently has Russian roots.

A man comes out of a bar in the middle of winter. Outside it is freezing, perhaps -12°C with a cutting wind driving the snowflakes.

He sees a man on his hands and knees under the streetlamp, clearly in a desperate search for something. So he decides to help, not wanting to see the poor soul exposed to the elements unnecessarily.

“Good evening friend, what ails you?” “I’m looking for my keys!”

The man gets closer to the ground and joins the search… “What do they look like? Do you have a keyring?” They continue the search in desperation as the cold wind cuts deeper and deeper.

Finally, the man is exasperated and asks: “Where did you last see your keys?”

“Over there where my car is parked” pointing to the far end of the parking lot.

Angrily the man then asks: “So why are you looking over here?!?”

Because this is where the light is.

We might laugh at this story, thinking how stupid the searcher was, but how is this different from so many ways in which we engage with our environment?

I was reminded of this the past week as I was shopping for a new printer. Searching and searching where the light is, google, amazon, camelcamelcamel.com

Like the man on his knees my search was constrained by the area around me circumscribed by the light of search engines.

Even though my need and the solution might be found somewhere else. I was blinded by what was presented.

In the last newsletter we discussed the almost sacred nature of attention. This discussion on consciousness in a way is an extension of that, looking at the impacts of contextual factors. Or the invisible dark matter of attention.

Context matters in subtle ways that we often overlook.

Data based

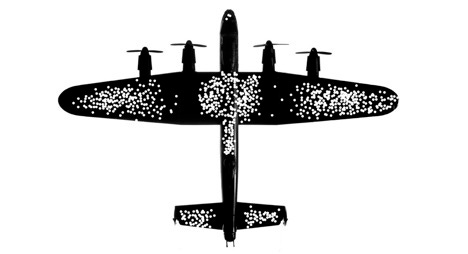

During the second world war, the American military had to make essential decisions about the application of scarce resources. One challenge they had was deciding how to apply reinforcement panels to their bombers.

The planes often came under attack from German Flak guns with devastating effect. The engineers proceeded to do what most people would do in this situation, they looked at the data.

In essence they looked at what the streetlight was revealing. What they saw was the following pattern of damage distribution:

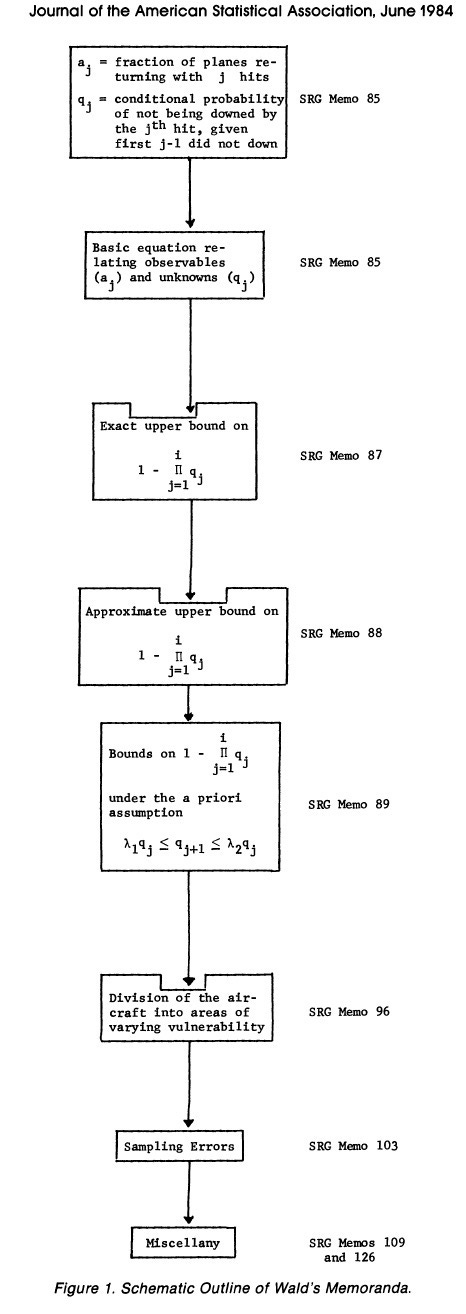

This became an easy mathematical problem. How would reenforcing the areas getting the most damage affect aerodynamics, fuel consumption and range. Enter the mathematician, Abraham Wald.

Wald hat a profound insight. He looked beyond the available data to see what was creating gaps in the data. He saw the missing bullet holes; he saw what was hidden outside the known parameters and comfortable illumination of the streetlight.

The Distribution of the holes represented areas that could successfully be hit and result in the return of the plane.

The missing holes were in the missing planes.

This phenomenon has now been turned into the mythology and internet meme “survivor bias.” A particular kind of observer bias, where the observer’s observations are biased by the data presented.

This kind of bias has shaped our world view from the most ancient times. We say the sun “rises,” we say that the tides come in and out (when in fact the water stays constant and dry land dips in and out of the deeper bits, suspended by the moon).

Our consciousness illuminates the world around it and, by so doing, defines the options we evaluate, consider, and learn from.

By looking outside of the cone of light he was able to see the underlying structure of the phenomenon and redefine the relationships between the evidence and the data.

Nothing personal

But how often are we trapped by the evidence in front of us? How often are we swayed by the tweet or instant message in front of us that confirms or contradicts our bias? Never considering the messages that were not sent or the context that allowed that particular message to come to light.

I clearly remember my first real performance review very well. After working for a year at Lindsay Smithers-FCB, my then boss called me in for the annual review to discuss how things were going and where my areas of improvement were.

Life felt pretty good back then for a 23-year-old who believed he could do no wrong. How quickly that illusion came crashing down. My boss explained something that really shocked me to the core. In many of the interactions with co-workers and colleagues my perception was that they were very friendly and helpful and that I had a good handle on managing creative work through the system as an account executive.

Little did I know that they were in effect just managing me. Quite a few of them could not stand me and decided the easiest way to get rid of me was simply to be nice and agree. After I left the room, their actions revealed a very different truth to the one I was experiencing.

I was suffering from a kind of survivor bias. My teammates were choosing the path of least friction and in so doing I never saw where the flak guns were really hitting or how my inputs had damaged their process. It was simply more efficient for them to treat me like a simpleton and complain to my boss once I was gone.

WYSIWYG

This was a very quick lesson in differentiating between reactions and results and has become a guiding principle for me in life.

We often frame our arguments and strategies on what we see: the reactions. The human desire for certainty will inherently drive us to limit what we look at in a way that reinforces our bias and emotional comfort. As John Lennon said, the more I see, the less I know for certain.

The reason is because “results” incorporate the action of unknowns. They prompt us to investigate what is not obvious.

In a VUCA world a bit of certainty is a lovely thing to cling onto but a fatal way to navigate.

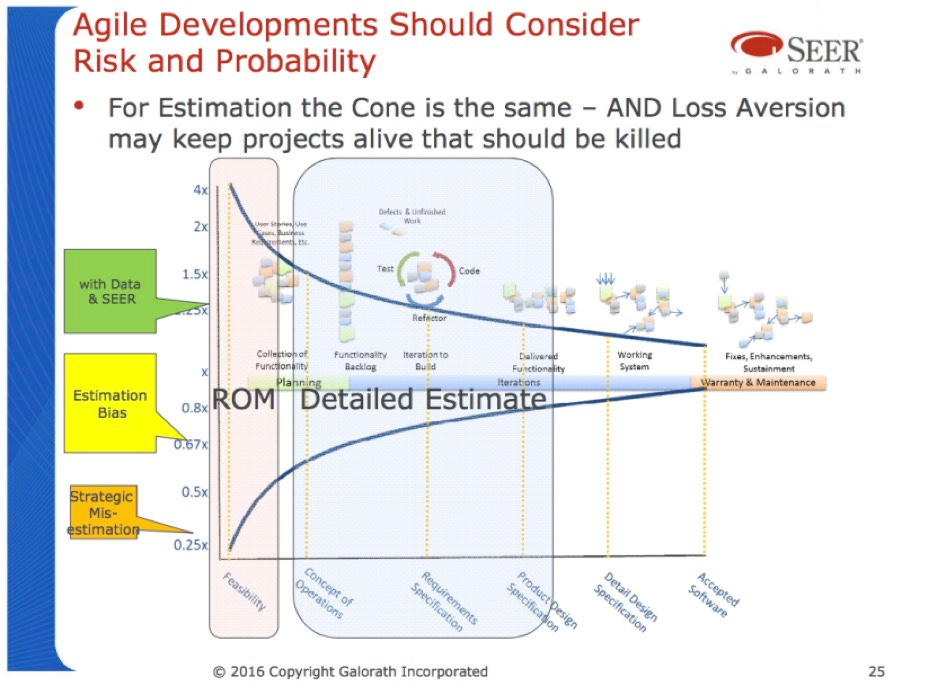

In this sense our consciousness creates a kind of “cone science” – facts and references establishing patterns and building bias inside our cone of observation. Our “cone of certainty.”

But what we don’t see might be the thing that kills us, or our project or company. The constant urge to embrace the discomfort of uncertainty, to choose discomfort over comfort is the only way to discover the 1 ton HIPPO under the water.

Can we flip the script on discomfort by understanding the true risk of “not knowing?” Can we live with the ambivalence that more data brings? Let’s find the keys outside the streetlight.

Let’s take that leap!

Three key take-outs:

1. Light

Are you aware of the landscape your consciousness circumscribes? Can you consciously describe where your awareness end?

2. Shadow

Can you embrace the darkness? What steps are you taking to increase your level of discomfort with “what you know”?

3. Shimmer

How do you deal with ambivalence? Can the shimmer of uncertainty light up new in-sight?